In Clinical

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

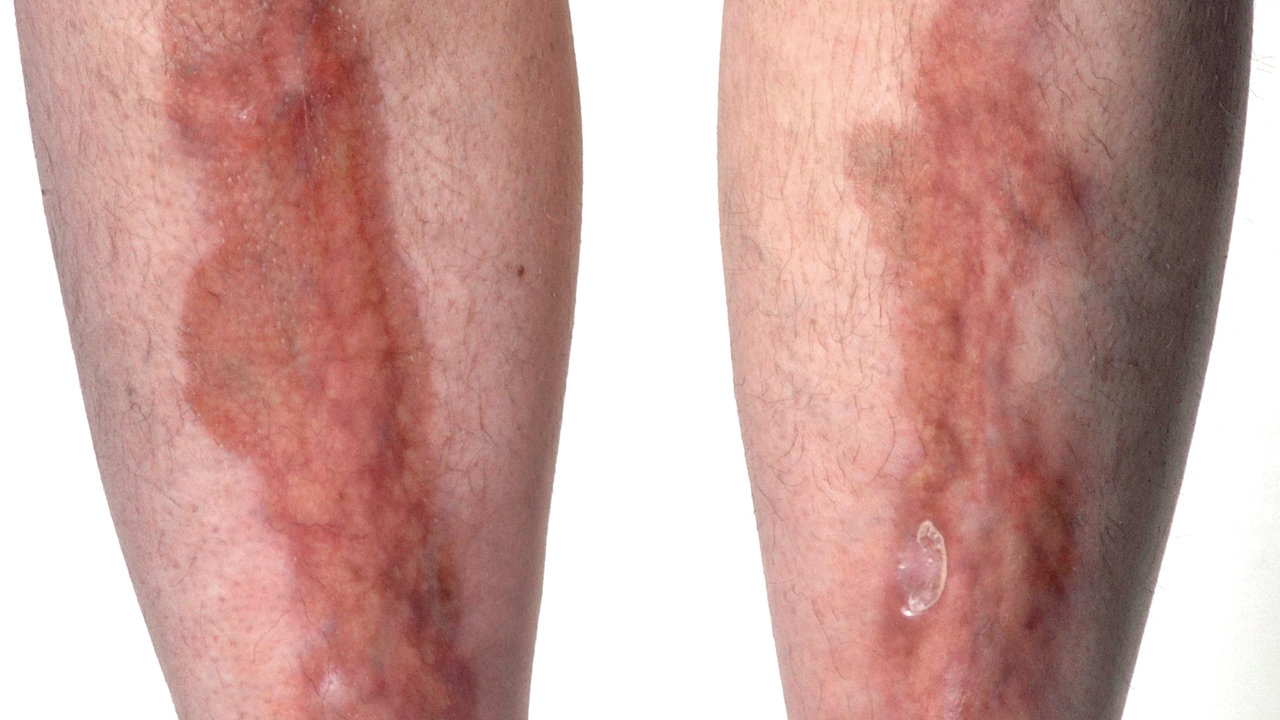

Necrobiosis lipoidica is an uncommon skin rash, most often seen in people with diabetes, which affects the lower part of the legs.

To put the prevalence into context, around one in every 300 people with diabetes will experience this condition, which is three times more common in women than in men.1 The rash usually starts as shiny, raised spots on the shins, which are reddish brown in colour. Over time, these lesions grow in size and join together to form larger patches with a red border, shiny yellow centre and prominent blood vessels.

Patients may report that the rash is painful or feels tender to the touch. As the surrounding skin is thin, minor trauma can lead to ulceration, turning the spots into open sores, which then increases the risk of subsequent infection.

The cause of necrobiosis lipoidica is not fully understood but is thought to arise from micro-angiopathy, which in turn leads to the breakdown of collagen fibres in the skin. Appearance alone is often sufficient for diagnosis and any customers suspected of having this skin condition should be referred to their GP as early treatment results in the best outcomes. Options for treatment include creams and ointments containing steroids or calcineurin inhibitors. In some cases, the condition may resolve spontaneously.

Hidradenitis suppurativa

Painful, boil-like lumps that appear in areas of the body that contain the apocrine sweat glands, such as the armpits, groin, breasts and buttocks, are characteristic symptoms of the skin disorder hidradenitis suppurativa (HS).

This condition arises due to blocked hair follicles, which leads to inflammation and a build-up of fluid and pus. Pus can then leak out through channels, known as sinus tracts, which develop under the skin. Abscesses, infection and scarring are also common complications of HS. Overall, HS affects only 1 per cent of the population.1 What causes the condition is unclear but smoking and obesity increase the risk substantially (around 60 per cent of HS sufferers are smokers).1,2

Hormones are another contributory factor as the disorder often onsets around puberty and may be associated with acne and hirsuitism. It occurs more commonly in women and in people of colour and may also be linked to inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, particularly if the groin and skin around the anus are affected.

In about one in three cases, there will be a family history of the condition.2 Unfortunately, HS presents as a recurrent and lifelong skin disorder that is complex to manage. Treatment options include topical antiseptics, oral antibiotics, retinoids and immunomodulatory medications including steroids and biologics. Surgery may even be warranted in severe cases.

Ichthyosis

Ichthyosis is a blanket term used to describe skin disorders that manifest as widespread build-up of rough, scaly skin. This phenomenon is known as hyperkeratosis and results from an impairment in the normal processes of skin regeneration.

Ichthyoses are typically inherited conditions but can also be acquired in patients with accompanying health issues such as malignancy, kidney disease or underactive thyroid.

Of the inherited types, ichthyosis vulgaris is the commonest, affecting around one in every 250 people.2 It usually onsets in early childhood (by one year of age) and typically produces mild symptoms such as fine grey-coloured scales on the upper and lower limbs, together with thickened skin on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet.

Concomitant eczema is common and symptoms tend to worsen when the weather is cold and dry. Autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis (ARCI) encompasses three rare and particularly severe types of ichthyoses, known as lamellar ichthyosis, congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma and harlequin ichthyosis.

Children with the first two types of ARCI gene are typically born within collodion membranes – a shiny yellow film stretched across the skin. Harlequin ichthyosis is characterised by diamond-shaped plates of thick skin all over the body and can be life-threatening.

Chronic inducible urticaria

Also known as physical urticaria, this is a type of skin disorder where the hallmark hive symptoms appear on the skin in direct response to an environmental stimulus such as pressure, heat, cold or vibration. Perhaps the most intriguing and also the commonest form of inducible urticaria is symptomatic dermographism, also known as dermographia.

In this condition – the name of which literally translates as ‘skin writing’ – lightly scratching the skin elicits raised red lines (wheals) that directly mirror where the skin was touched. These marks appear within a few minutes of pressure being applied to the skin and disappear within 30 minutes if the stimulus is removed.

Management of inducible urticaria centres on identifying and avoiding the physical triggers. Antihistamines can also be used to help dampen down the symptoms. Similar to other urticarias, sufferers should be advised to avoid known skin irritants, try not to scratch at the skin and keep the skin well hydrated using simple non-perfumed moisturisers or emollients.

Actinic prurigo

Caused by a photosensitive reaction to sunlight, the intensely itchy rash of actinic prurigo typically occurs on sun-exposed areas of the skin. The rash can appear hours or days after sunlight exposure as red/pinkish inflamed lumps, which quickly become excoriated, crusted and scabbed. The lips and eyes can also be affected.

Actinic prurigo is a rare condition, affecting fewer than one in 1,000 individuals and usually onsets in childhood or adolescence.1 Unsurprisingly, symptoms of actinic prurigo tend to be worse in the spring and summer months.

The precise cause is not known but emerging evidence suggests that an allergic reaction to proteins altered in sunlight in people with specific inherited genes could be to blame.

UV protection is the cornerstone of actinic prurigo management, which includes covering the skin with clothing, wearing a hat and applying high SPF sunscreen. Sufferers may also benefit from taking a vitamin D supplement to avoid potential deficiency resulting from avoidance of sunlight.