Is coffee really bad for us?

In Population Health

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

A daily coffee or two is a ritual for many people, but it can be compared to having a vice or an addiction – not helped by alarmist headlines in newspapers. But is coffee really that harmful?Â

I’m willing to bet that many of you read TM over a cup of coffee. But you could be forgiven for wondering how safe coffee really is. Last year, for example, a study suggesting that “more than four cups of coffee a day could send you to an early grave†hit the headlines. Men aged under 55 years who drank more than 28 cups a week were 56 per cent more likely to die during the 17-year study than those who didn’t consume coffee. Women were about twice as likely to die. And we know that too much coffee can trigger panic attacks, anxiety, headaches, and, especially if drunk late at night, poor sleep.

But before you tip the rest of the cup down the sink, it’s worth taking a peak behind the headlines. People who drink very high levels of coffee may have unhealthy lifestyles or a genetic makeup that might partly account for the headlinegrabbing link. In fact, moderate coffee consumption seems to protect against numerous ailments, including Parkinson’s disease, gallstones and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), such as strokes and heart attacks.

Healthy stats

Drawing conclusions from a single study is often difficult – partly because the amount of caffeine and other chemicals varies depending on the particular bean, whether you drink from a mug or cup, and the way it’s brewed (see box opposite). So, scientists increasingly use metaanalyses, which merge data from several studies, to help iron out such wrinkles. The results are reassuring for coffee-lovers. One meta-analysis looking at coffee’s effect on CVD included almost 1.3 million people from 36 studies.

The researchers separated people into four groups based on the amount of coffee they drank: none, low (typically, people in this group drank 1.5 cups of coffee a day), middle (typically 3.5 cups) and high (5 cups). Compared with people who did not drink coffee, the low and middle groups were 11 per cent and 15 per cent less likely to develop CVD respectively. However, those with a high intake were five per cent less likely to develop CVD.

In other words, coffee had a U-shaped influence: the risk fell, but then increased again. This U-shape emerged for the risk of developing coronary heart disease (CHD) – the build up of fat in the blood vessels supplying the heart, which is the main cause of heart attacks – and strokes. Low, middle and high consumption cut CHD risk by 11 per cent, 10 per cent and seven per cent respectively. For stroke, the reductions were 11 per cent, 20 per cent and five per cent respectively.

Coffee may also protect against type 2 diabetes – the most common form of the disease, which is strongly linked to being overweight. According to a meta-analysis that included 26 papers and about 1.1 million people, an extra two cups of coffee reduced the risk of type 2 diabetes by 12 per cent. Drinking an extra two cups of decaffeinated coffee reduced the risk by 11 per cent.

These benefits might help explain why a meta-analysis that included 21 trials encompassing 997,464 people found that those who drank four cups daily were 16 per cent less likely to die from any cause. And drinking three cups a day seemed to have the biggest effect on CVD death, cutting mortality by a fifth (21 per cent). But coffee consumption did not influence deaths from cancer.

Another meta-analysis included 17 studies and about 1.1 million people. Again, researchers reported a U-shaped relationship between coffee consumption and deaths from any cause. Drinking between one and three cups a day cut overall deaths during the studies by 11 per cent compared to non- or occasional drinkers. Those drinking three to five cups were 13 per cent less likely to die, while deaths declined by 10 per cent in people drinking at least five cups. Women benefited especially: reductions were 16 per cent for one to three cups, 19 per cent for three to five cups and 15 per cent for at least five cups. In men, the reductions were nine per cent, 10 per cent and 6 per cent respectively.

Here comes the science

Researchers still do not fully understand why coffee seems to reduce the risk of several diseases. But their confusion is not really surprising. After all, coffee is a complex chemical cocktail: more than 1,000 chemicals contribute to coffee’s aroma, for example. However, coffee – along with tea and cocoa – is rich in a group of chemicals (polyphenols) that seem to reduce blood pressure, lower levels of cholesterol in the blood, increase sensitivity to insulin (which can counter diabetes), and prevent inflammation. Decaffeinated coffee contains as much, if not slightly more, polyphenols than regular coffee.

The most abundant polyphenols are chlorogenic acids, which contribute to coffee’s bitter taste and trigger the indigestion some drinkers experience. The amount of chlorogenic acids in a cup of coffee varies widely (20–675mg per cup) partly depending on the type of bean, its preparation and how the coffee’s brewed. But chlorogenic acids are potent antioxidants which mop up tissue-damaging free radicals. This might also contribute to coffee’s benefits.

Despite these benefits, stopping the regular consumption of even small amounts of caffeine (about 100mg) can produce mild withdrawal symptoms in some people. Sensitive people may experience, for example, anxiety, low mood, nausea, vomiting and, most commonly, headaches and tiredness. Symptoms begin to emerge about 12 hours after the last drink and peak after one or two day’s abstinence. So, if you suffer on weekends, it might be because you drink less coffee at home than when you’re at work.

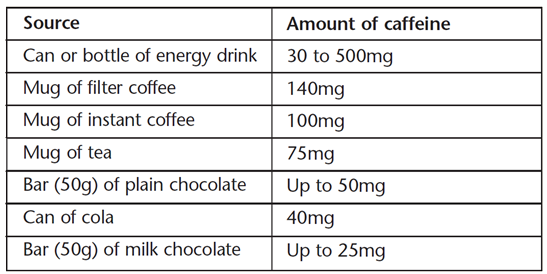

Pregnant women should consume no more than 200mg of caffeine a day: too much caffeine during pregnancy increases the risk of low birthweight and miscarriage. But for the rest of us, drinking up to about 400mg of caffeine a day (the amount in four or five cups of coffee) probably won’t do any harm – whatever some headlines might have you believe. Moderate consumption might even do you some good. So, enjoy your coffee… although you might want to think twice about the biscuit.

Â

What's in a cup?

In 2001, the Food Standards Agency analysed 400 samples of tea and coffee bought from cafés, shops and so on, or brewed at home or work. The amount of caffeine varied widely. Tea contained, on average 40mg caffeine. However, caffeine content ranged from 1-90mg. Instant and ground coffee contained, on average, 54 and 105mg caffeine respectively. But the amount ranged from 21-120mg and 15-254mg a serving respectively.